October 1929: The Bottom Falls Out

October 24, 1929 marked a major turning point in US and world history as the New York Stock Exchange saw the biggest single-day drop in its history. Though the warning signs had cropped up through the preceding spring and summer, nothing could prepare the public for the calamity that eventually occurred. The 1929 Crash, its causes, and consequences still echo in today’s culture as the onset of the Great Depression.

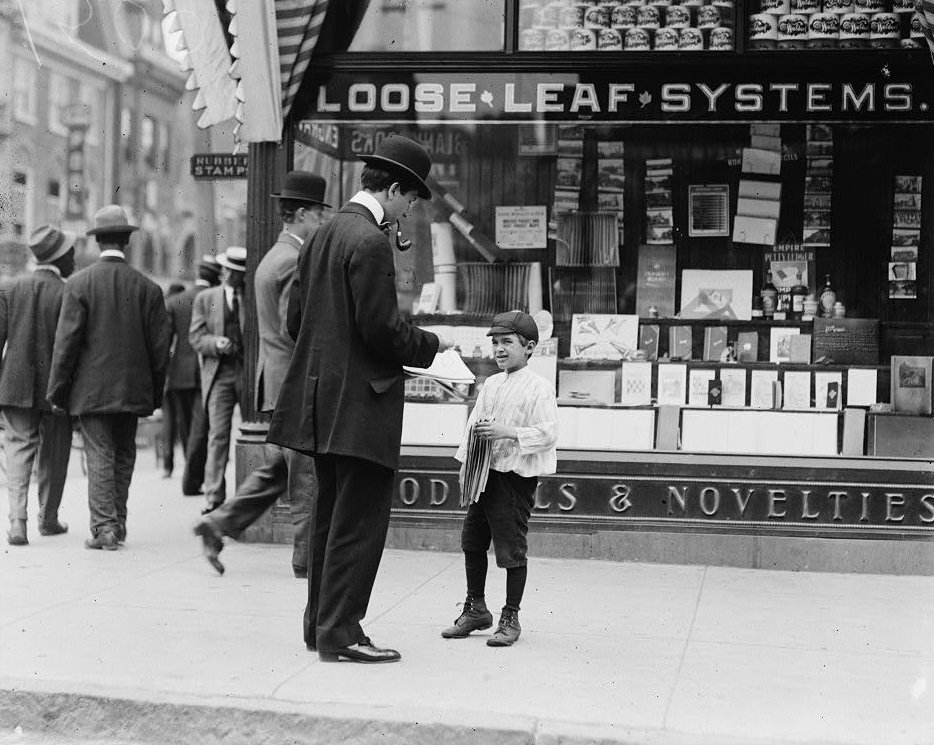

The Roaring 20s: A Bull Market

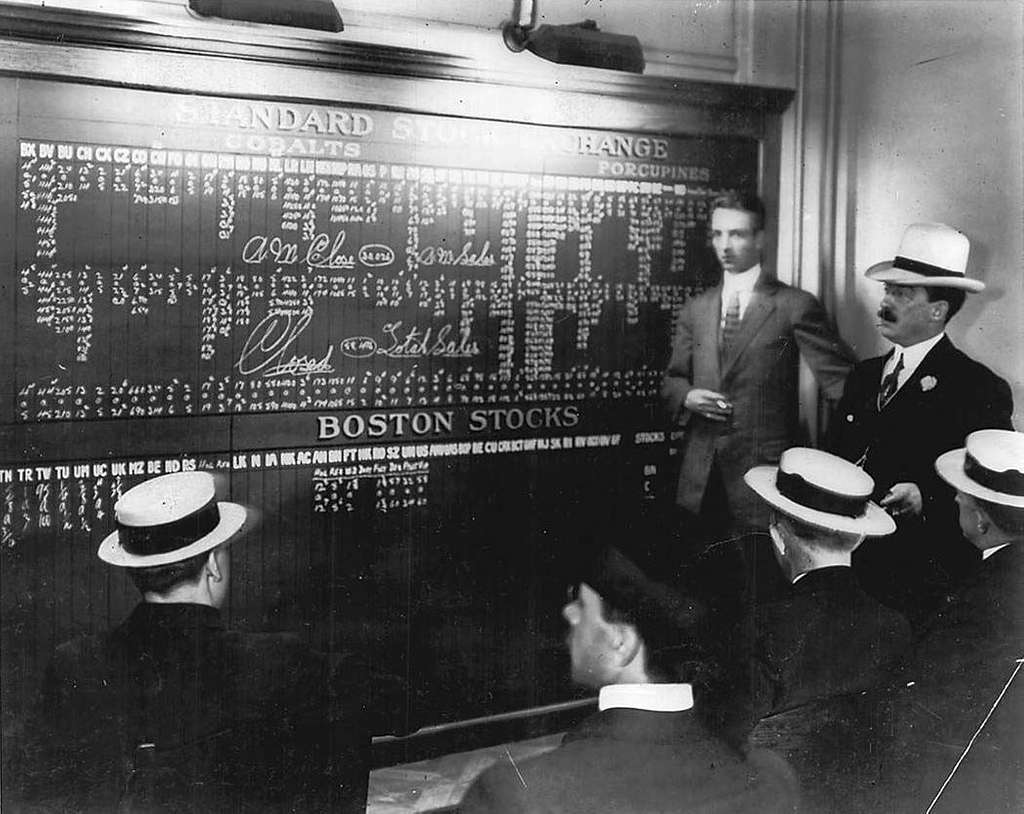

The decade of the 1920s in the United States is remembered today for its rapid economic growth, the development of mass popular culture, and increased consumerism. These trends were also marked by a major upswing on the stock market, as it became much more common for middle- and working-class people to buy and sell shares.

National Woman's Party, Wikimedia Commons

National Woman's Party, Wikimedia Commons

Wild Optimism

The stock market grew steadily throughout the 20s, leading to the general belief that the market would grow forever. The buoyant public mood led more and more people to put their money in the market, confident of gaining big returns.

Investment Vs Speculation

As share prices rose steadily through the 20s, a growing number of people began speculating on the stock market. Instead of investing in businesses based on fundamentally sound long-term business principles, these buyers sought to play the market for short-term gains.

The Strong Hand Of The Federal Reserve

Concerned about the growth of a stock market bubble, the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates in 1928 and early 1929. The economic growth in the US began to level off.

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

Stock Market Bubble Vs Economic Reality

The stock market continued to rise, growing out of proportion to other parts of the economy, which began to slow in 1928 as the interest rate hikes led to a drop in home and car purchases.

March 25, 1929: The First Shock Wave

This day saw the first indication of what was to come later in the year, as numerous investors were wiped out in a wave of selling. Many of them had bought into the market on margin, i.e., using borrowed funds. Selling at a loss, they were forced to liquidate assets to pay back creditors.

Charles Mitchell’s Bold Move

The sudden jolt to the market was leading many to seriously question whether the market was on solid ground. Into this vacuum of uncertainty stepped flamboyant New York banker Charles Mitchell. On March 27, Mitchell issued $25 million of his bank’s money to traders to halt the slide.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

The Climb Resumes

Mitchell’s decisive move enabled traders to stem the sell-off and maintain stock price levels. The market seemed to recover, and as the spring went on, the market began to move upward once again.

Peak Performance

As the summer progressed, the bull market resumed in full force. Between the beginning of June and September 3, 1929, the Dow Jones average climbed 20% to a record 381.17, a tenfold increase over its 1920 level. Nevertheless, manufacturing and home construction continued to stagnate.

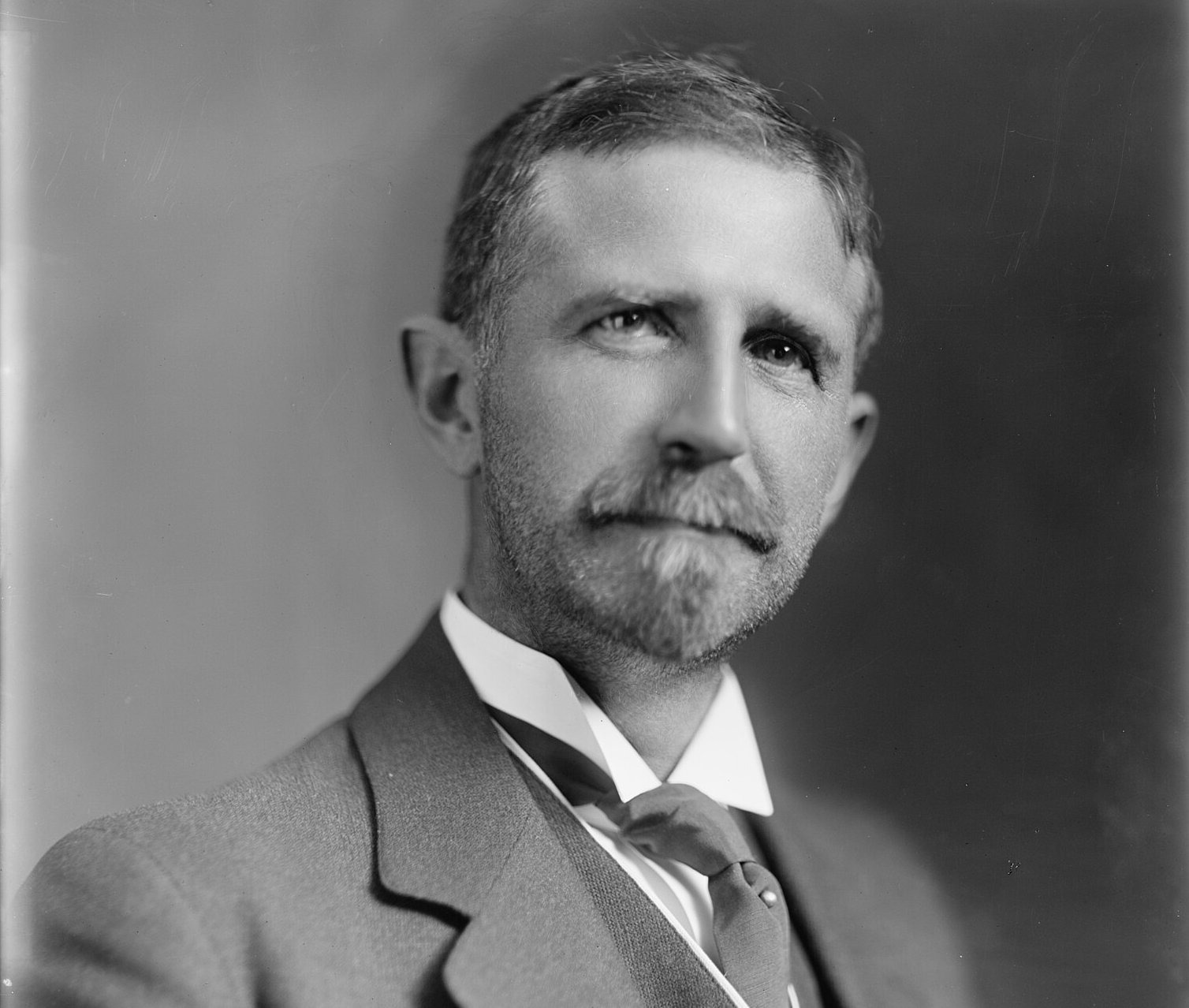

Roger Babson Speaks Up

Roger Babson was an early teacher and practitioner of sound investment principles. He taught “value investing” mastermind Benjamin Graham, who in turn mentored Wall Street wizard Warren Buffett. By the fall of 1929, Babson had grown increasingly disenchanted with the manic stock market bubble that was inflating beyond all reason.

Harris & Ewing, Wikimedia Commons

Harris & Ewing, Wikimedia Commons

The Babson Break

Babson had had a bearish outlook for the previous two years that went largely unheeded by the press and public. That all changed on September 8, when he stated in a speech that “sooner or later a crash is coming, and it may be terrific”. The response was immediate as the market went into a downturn through September, a drop that the press dubbed “The Babson Break”.

Bear Market Or Temporary Correction?

As September 1929 drew on, the plunge triggered by Babson’s cautionary words leveled off, as the media and public regarded the dip as a short-term market correction. Advertised as a buying opportunity, prices seemed to recover into October, though volatility and uncertainty continued.

U.S. National Archives, Picryl

U.S. National Archives, Picryl

Words That Would Come Back To Haunt

In an October 15 speech to an industry association, famed Yale University economist Irving Fisher announced that stock prices had reached “a permanently high plateau”. Fisher’s optimistic remarks would damage his academic and public prestige for generations to come.

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

A Roller Coaster Ride For Investors

The increasing public attention on the markets and the conflicting views of influential investors contributed to a drastic growth in trading volumes and market volatility as October entered its last week.

National Archives Photo, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives Photo, Wikimedia Commons

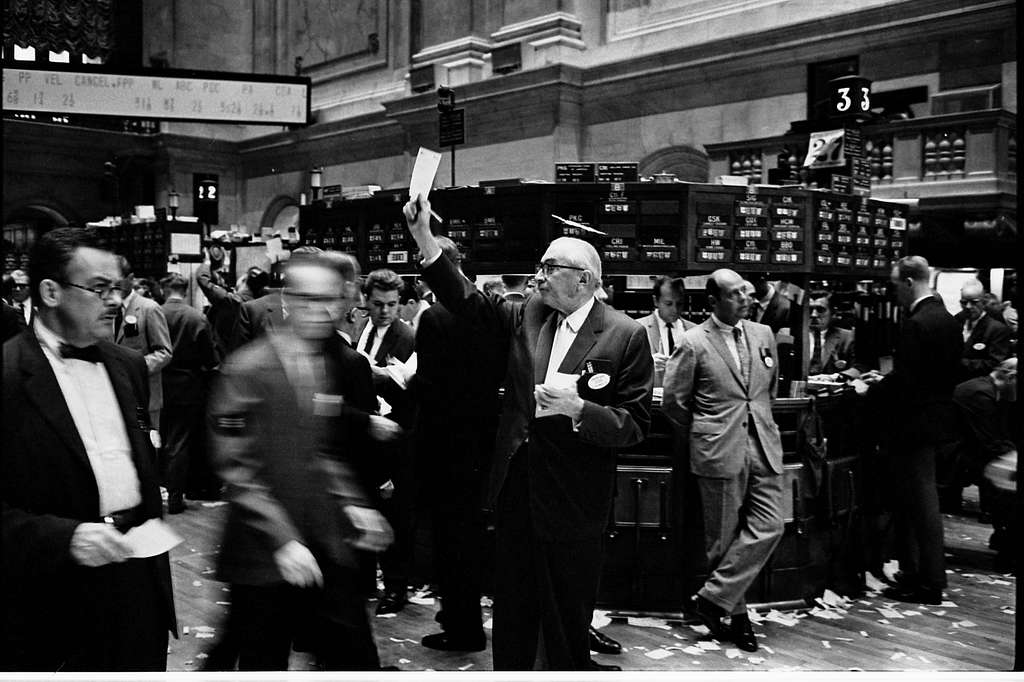

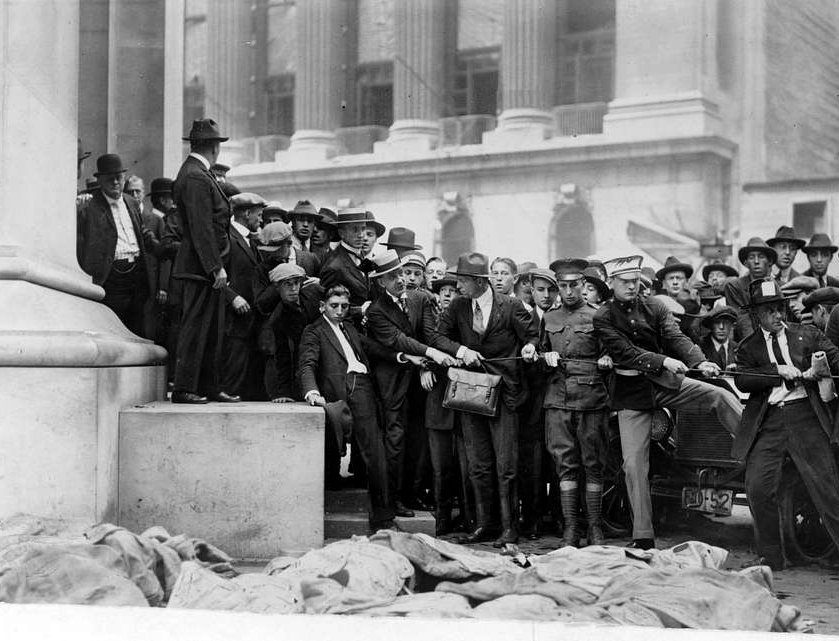

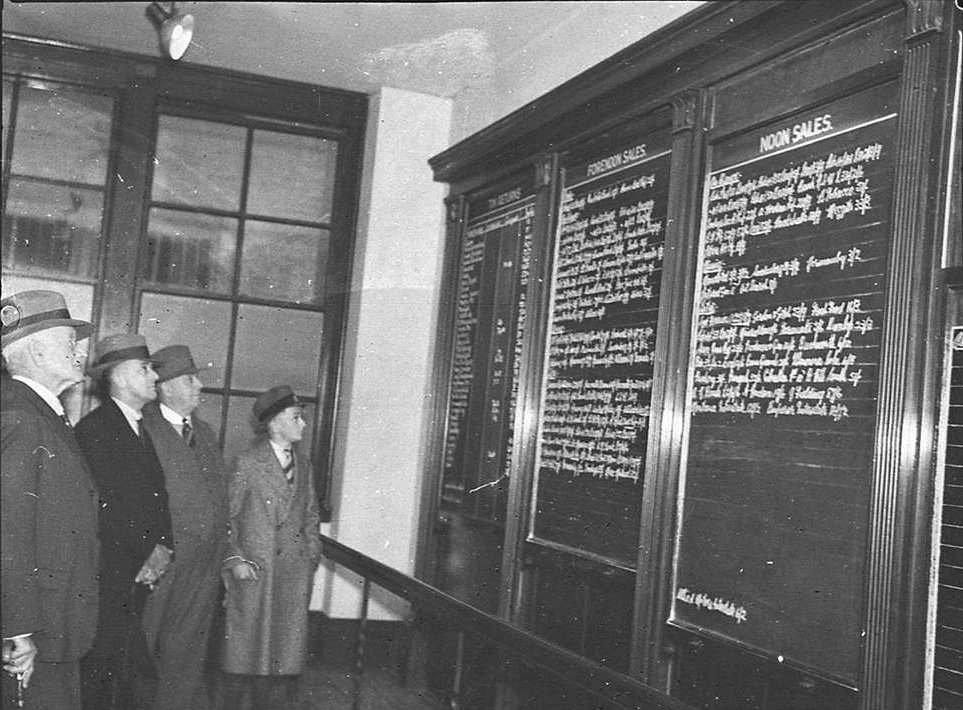

Black Thursday: A Wave Of Panic

October 24 marked the infamous Black Thursday, a day on which the stock market lost 11% of its value at the opening bell. Trading volumes were so heavy that the ticker tape machines that tracked stock prices fell hopelessly behind, meaning that out-of-town brokers had no idea how much shares were selling for, even in the rare case that they could find a buyer.

Associated Press, Wikimedia Commons

Associated Press, Wikimedia Commons

Damage Control

The confusion and losses of Black Thursday were clear indications that action needed to be taken. Three prominent Wall Street investment bankers decided that the time had come to act before the chaos on the trading floor got completely out of hand. These were: Thomas W Lamont of Morgan Bank; Albert Wiggin of Chase National Bank; and Charles Mitchell, whose $25 million infusion had halted the market’s slide back in late March.

Chris Li chrisli, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Chris Li chrisli, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Meeting Of The Minds

The influential Wall Street trio, with New York Stock Exchange vice president Richard Whitney acting as their representative, purchased 25,000 shares of US Steel at $205 apiece. The price they paid was significantly higher than the current official share price. The group made similar buys of other blue-chip stocks in an attempt to emulate the tactics that had averted a near-meltdown of the market back in 1907.

Associated Press, Wikimedia Commons

Associated Press, Wikimedia Commons

Disaster Averted (For Now)

The aggressive moves of the wily Wall Street money men seemed to pay off. The market closed on Black Thursday down only 2.1% for the day, having rallied back from that morning’s bedlam. It had taken a billion dollars of the group’s money, but disaster had been averted—at least for the time being.

A Brief Respite

Friday, October 25 saw the market make minor gains as that day’s edition of the Wall Street Journal congratulated Lamont, Wiggin, and Mitchell for their actions the day before. However, investors and the general public were clearly still stewing over the previous day’s events and would continue to do so over the weekend.

Black Monday Brings More Carnage

It soon became evident on the morning of Monday, October 28 that any relief from the previous Thursday’s troubles would be short-lived. The market plunged 12.82% on the day, a record single-day loss for the Dow Jones average.

Black Tuesday: A Stampede For The Exit

The decision by many to sell their positions and escape the downward plunge had become a panic-stricken frenzy. By the end of Black Tuesday, October 29, the grim news had become catastrophic. The market was down an additional 11.73%, wiping out $14 billion in capitalization. The two-day loss totaled over 23% of the market’s value.

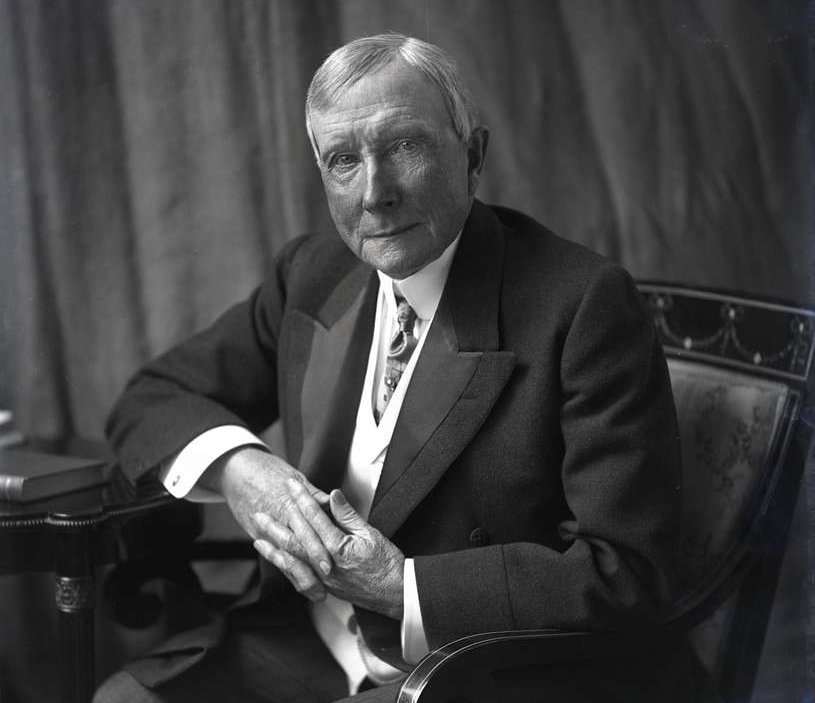

Unprecedented Trading Volumes

Recall that the entire week had seen record trading volumes as frantic brokers tried to cut their losses. Titans of industry now attempted corrective measures—on Tuesday, General Motors founder and chairman William C Durant coordinated with members of the wealthy Rockefeller family to buy large blocks of shares, but this failed to halt the slide.

Wednesday Sees A Rebound

The markets saw a sharp upswing on Wednesday, as the index jumped 12.34%, but this rally turned out to be an anomaly, and the stock market went into a steady two-week decline that would bottom out at 198 points on November 13.

Reviewing The Numbers

The 198 level of the Dow Jones industrial average (the index of the stock market’s value) at close on November 13, 1929 represented a loss of over 100 points since the morning of October 28, or a 33% loss in just over two weeks. If we use the September 3 peak of 381 as the starting number, the market had lost almost half its value in a little more than two months. Roger Babson’s words had been prophetic: The crash had been terrific.

Bear Market Rally

Little remembered today, the market made a slow, agonizing climb back to the 294 level by April 17, 1930. Though this was near the levels seen before Black Monday, this did little to comfort the many investors who had left the market after having lost everything. The damage to public confidence and the worsening situation in the general economy eclipsed any good news coming from Wall Street.

Descent To Rock Bottom

The bear market rally over the winter of 1929-30 would prove to be illusory, as the stock market descended steadily for two years to an all-time low of just 41.2 points on July 8, 1932. This number remains the lowest level reached in the 20th century, indicative of its time period in the Great Depression.

Picking Up The Pieces

In the months and years following the 1929 Crash, the financial community was left to figure out how things had all gone wrong. There was a period of significant reflection as stock markets and governments made changes to try to prevent similar crashes in the future.

National Photo Company, Picryl

National Photo Company, Picryl

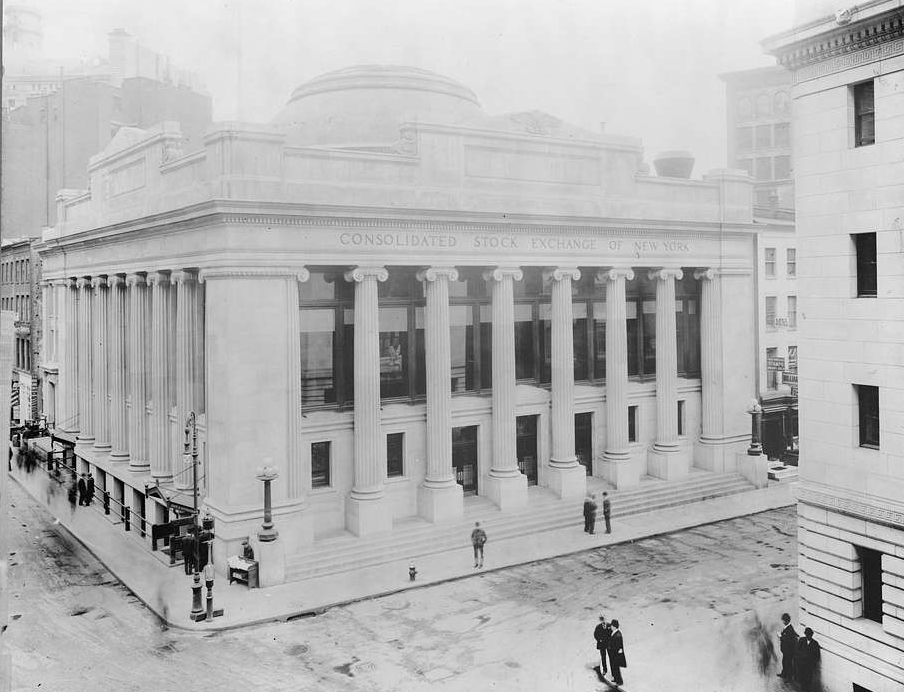

The Post-Mortem Begins

The first step in preventing future crashes was to pinpoint the causes of the 1929 Crash. The US federal government established a senate committee called the Pecora Commission in 1932 to comb through the wreckage and establish the major factors underlying the collapse.

Corrupt Banking Practices Identified

The Pecora Commission zeroed in on many of the practices of banks in the lead-up to the crash and found an industry rife with conflicts of interest. Banks were often underwriting unsound securities to settle bad loans, and many were using commercial deposits to speculate in the stock market.

The Glass-Steagall Act

An enduring result of the Pecora Commission’s findings was the establishment of the Glass-Steagall Act which separated the activities of regular banks from that of the investment banks. The Act’s provisions would not be relaxed until the late 1990s.

SEC Established

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was established by the Roosevelt administration in 1934 as part of its New Deal program to tackle the Great Depression. The SEC enforced greater financial transparency on publicly traded companies and established a uniform national set of regulations for securities trading.

Markets Adapt

Further into the 1930s and in the days since, stock markets worldwide have tended to suspend trading in the event of a crash. This has not entirely prevented further single-day crashes like that of October 19, 1987, however, it allows markets to contain the damage and quickly recover.

Looking Back On The Bubble

Most analysts today regard the 1929 Crash as the result of the speculative boom of the 1920s. The economy was growing quickly, leading to record profits on a yearly basis. This led to blind optimism about the limitless future growth potential of the economy.

Mass Speculation

Speculation in the stock market had always been viewed by the general culture as a specialized and highly risky activity conducted only by professional investors. The growth of the market and its spectacular returns led to a much larger pool of “regular people” trying to play the speculation game.

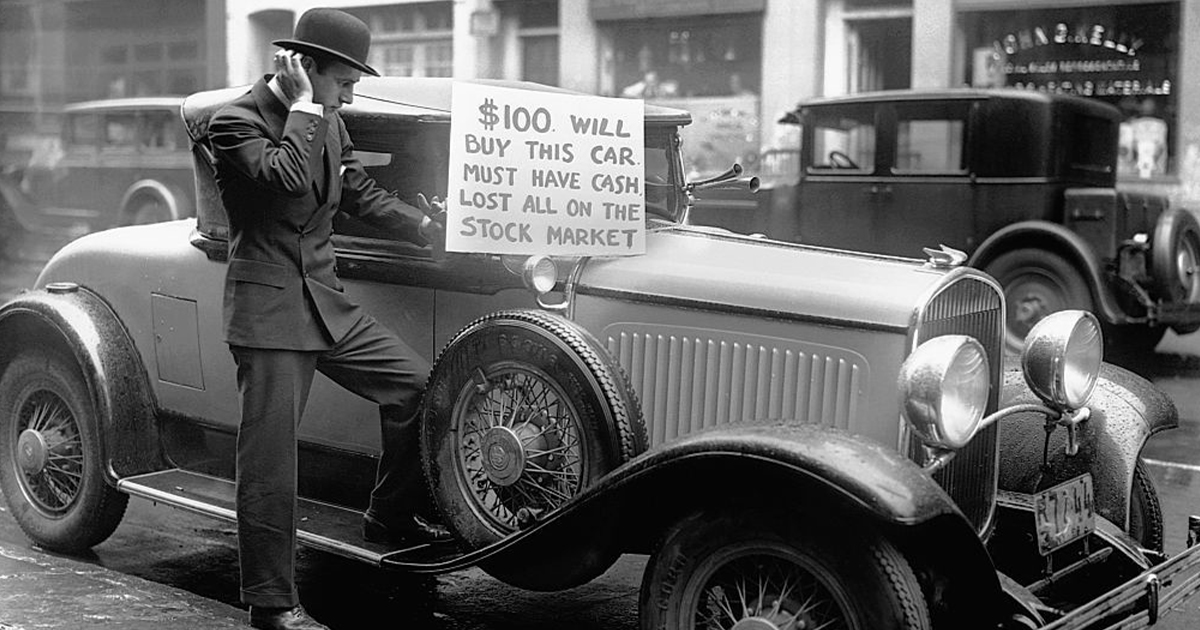

Buying On Margin

Not only were more people trying to get into the market, but a huge proportion of them were buying shares on margin. Margin buying involves borrowing money from a broker to make the purchase, using the acquired shares as collateral for the loan. This magnifies the loss if the share price goes down.

Margin Buying At Flood Tide

It is now estimated that small investors were commonly borrowing two thirds of a share’s value from their brokers by August 1929. This margin buying reached an estimated $8.5 billion, more money than was then even circulating in the US economy! It didn’t take a financial genius to know what would happen to that money if the market went south.

Irrational Exuberance

A further clue that a bubble had developed by the fall of 1929 could be seen in the market’s price-to-earnings ratio. This measures the amount of money in the market against the ability of companies to make further gains. The ratio stood at 32.6 by September 1929—not a record number by any means, but well above its historical average.

Were People Really Jumping Out Of The Buildings?

The 1929 Wall Street Crash was a terrible day for all of America, but there were reports that some stockbrokers’ reactions were more disturbing than anyone could have imagined. One of the lasting popular images of the 1929 Crash is the rash of suicidal investors and financiers plunging to their deaths from the windows of skyscrapers. But is it really true?

Not according to author John Kenneth Galbraith, whose research for his 1955 book The Great Crash, 1929 established that the rumors were mainly a result of erroneous British newspaper reports.

Symptom Of A Deeper Sickness

Though popular culture remembers the 1929 Crash for bringing about the Great Depression, economic historians argue that a slowing economy and international trade were the true culprits. This view holds that the shocking October implosion was merely the first visible symptom of an economy already in the early stages of a depression.