Lost professions

Decades and centuries before switches and automation shaped daily routines, entire professions solved problems modern life no longer notices. These jobs were practical and once essential, but each disappeared for a reason tied to progress or convenience.

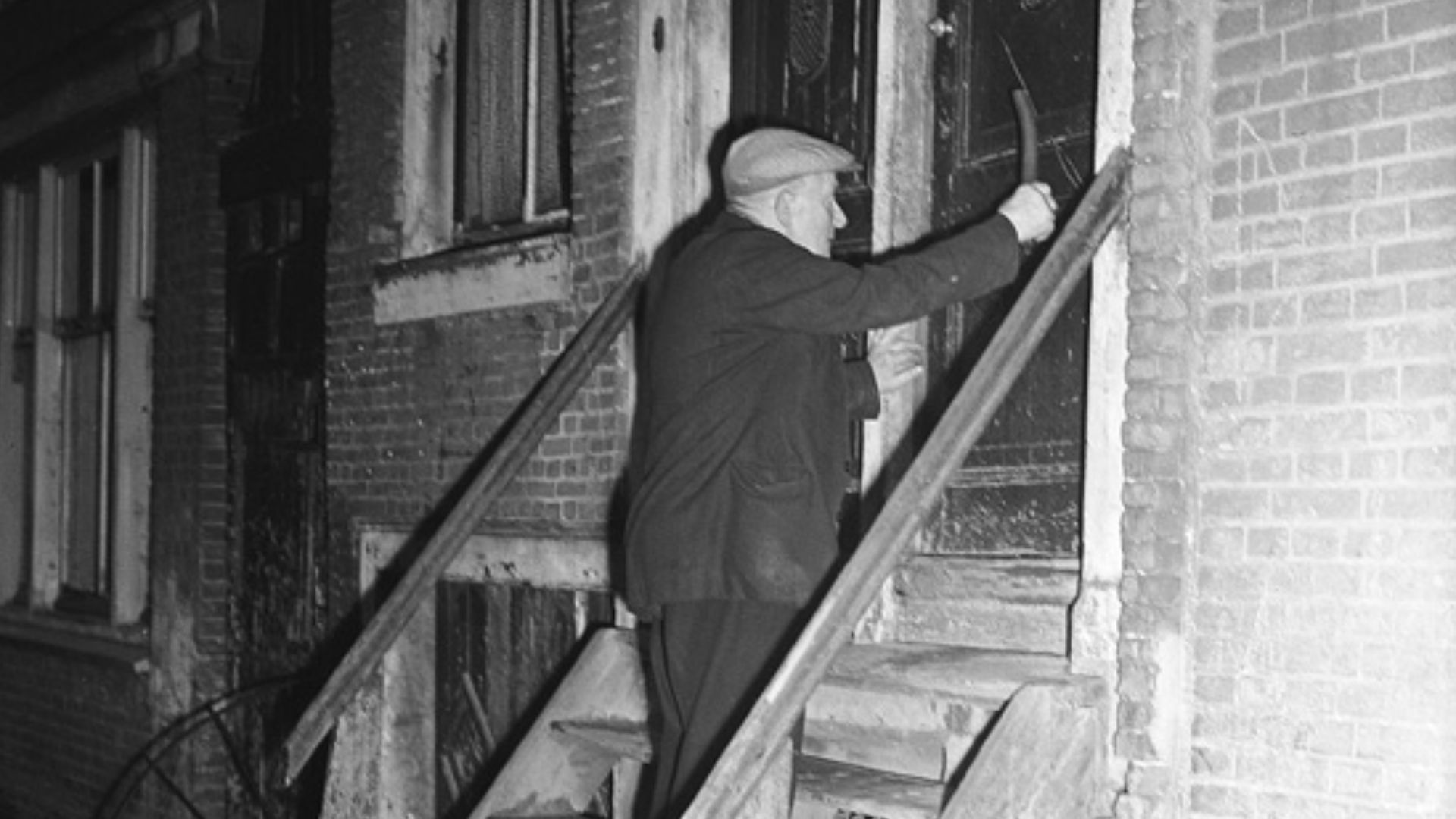

Knocker-Up

Industrial workers relied on knocker-ups to start the day years before the invention of alarm clocks. Emerging during the Industrial Revolution, these early human alarms used sticks, batons, or pea-shooters on windows. Many refused to leave until clear proof appeared that their client was awake.

Lamplighter

Electric grids transformed cities, but years earlier, lamplighters walked streets every evening and morning, lighting and extinguishing lamps. From the 16th century onward, their work involved refueling oil or gas fixtures and replacing mantles. In some towns, the same individuals quietly served as informal night watchmen.

Gunnar Lanz, Wikimedia Commons

Gunnar Lanz, Wikimedia Commons

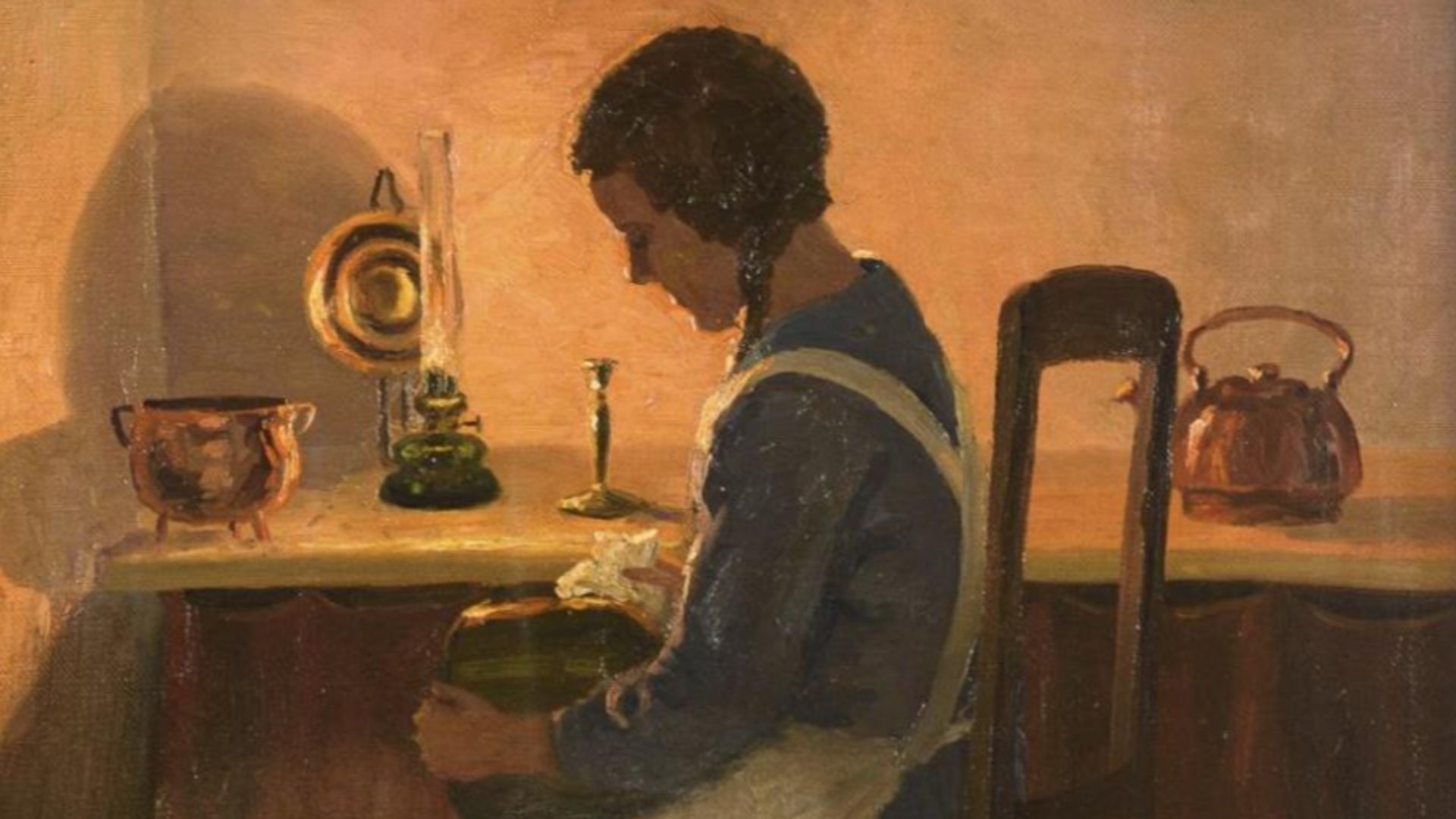

Leech Collector

Medical bloodletting created a steady demand for leech collectors during the 18th and 19th centuries. To gather them, workers often stood barefoot in bogs or marshes and let leeches attach to their own legs, risking infection and blood loss.

Jim Griffin , Wikimedia Commons

Jim Griffin , Wikimedia Commons

Ice Cutter

Each winter, ice cutters carved massive blocks from frozen lakes and rivers to preserve food year-round. The ice was stored in insulated houses, then delivered directly to homes. Trade records even classified ice as a legal crop. Mechanical refrigeration in the 20th century quickly collapsed the entire industry.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Resurrectionist

In 18th and 19th-century Britain, resurrectionists supplied anatomists with stolen bodies due to a severe shortage of legal cadavers. Operating at night, they exhumed the recently buried until the practice was outlawed.

Keppler, Udo J., 1872-1956, artist, Wikimedia Commons

Keppler, Udo J., 1872-1956, artist, Wikimedia Commons

Switchboard Operator

Early telephone networks depended on switchboard operators who manually connected calls by plugging wires into jacks. It became one of the fastest-growing jobs of the early 20th century. Women dominated the field and even served overseas during WWI.

Seattle Municipal Archives from Seattle, WA, Wikimedia Commons

Seattle Municipal Archives from Seattle, WA, Wikimedia Commons

Powder Monkey

On warships, powder monkeys were young boys, usually aged twelve to fourteen, tasked with carrying gunpowder from magazines to cannons during battle. Their small size allowed movement through cramped decks. Despite the danger and importance of their work, they held no official naval rank.

Civil War Glass Negatives, Wikimedia Commons

Civil War Glass Negatives, Wikimedia Commons

Gong Farmer

During the peak of Tudor England, gong farmers handled one of society’s least desirable necessities by removing human waste from cesspits. Because of the stench, authorities restricted the work to nighttime hours. The term “gong” was Old English slang for both feces and toilets.

Lector

Inside cigar factories, especially in Cuba and Florida, lectors were hired to read aloud while workers rolled cigars. Newspapers, novels, and political texts filled long workdays, and employees democratically voted on reading material. The role declined in the 1920s as radios spread and factories became increasingly mechanized.

Henri Atelier, Wikimedia Commons

Henri Atelier, Wikimedia Commons

Telegraphist

Telegraphists formed the backbone of long-distance communication during the 19th and early 20th centuries by sending Morse code through telegraph keys. Their work connected ships and nations. After the Titanic disaster, regulations required trained telegraphists aboard vessels.

Creator:Olive Edis, Wikimedia Commons

Creator:Olive Edis, Wikimedia Commons

Pinsetter

Today, automation controls bowling alleys, but back in the day, pinsetters manually reset pins after every frame. Teenage boys held these positions and usually worked in loud, dangerous conditions behind the lanes. Many alleys called them “pin boys,” and they were known for sneaking free games.

Lewis Wickes Hine, 1874-1940, photographer., Wikimedia Commons

Lewis Wickes Hine, 1874-1940, photographer., Wikimedia Commons

Groom Of The Stool

Serving in Tudor England, the Groom of the Stool assisted the monarch with personal hygiene. Despite the task’s intimacy, the position granted constant access to the king, allowing holders to become trusted political advisors.

Anthony van Dyck, Wikimedia Commons

Anthony van Dyck, Wikimedia Commons

Gandy Dancer

Railroad maintenance crews known as gandy dancers kept tracks aligned during the 19th and 20th centuries. Using heavy hand tools, they manually tamped and adjusted rails. Their coordinated movements were matched with rhythmic chants that later inspired folk songs.

Edward Hungerford, Wikimedia Commons

Edward Hungerford, Wikimedia Commons

Powder Tester

Powder testers ensured gunpowder quality for military and mining use by measuring burn rates and conducting ignition trials. Some tests involved small cannons called eprouvettes. The work required precision but carried risk. Advances in chemical analysis and standardized production eventually made this hands-on testing method unnecessary.

Photographed by User:Bullenwächter, Wikimedia Commons

Photographed by User:Bullenwächter, Wikimedia Commons

Quarrymen

Stone extraction once depended on quarrymen who cut and blasted rock using hand tools and carefully placed explosives. Their work fed the rapid growth of cities and large infrastructure projects, where whistles or flags warned others before blasts.

Alehouse Scullion

Behind the scenes of medieval and early modern taverns, scullions performed the cleaning and heavy chores that kept alehouses running. Many were young servants or apprentices paid with food and lodging instead of wages.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Candle Dipper

For years, candle dippers built light by hand. Wicks were repeatedly dipped into molten tallow or wax until the proper thickness formed. The work remained essential until industrial molding and electric lighting spread. Many candle dippers belonged to guilds that enforced strict rules on wax quality.

Herald Painter

In medieval and Renaissance Europe, herald painters created coats of arms, banners, and heraldic symbols for noble families. These images served as a visual identity before widespread literacy. As printing presses and modern graphic design emerged, demand declined.

CEphoto, Uwe Aranas, Wikimedia Commons

CEphoto, Uwe Aranas, Wikimedia Commons

Whalebone Corset Maker

Fashion between the 16th and 19th centuries relied on whalebone corset makers to shape garments using baleen for structure. The same material supported umbrellas and buggy whips, tying corset work to a wider trade network.

Eugène Atget, Wikimedia Commons

Eugène Atget, Wikimedia Commons

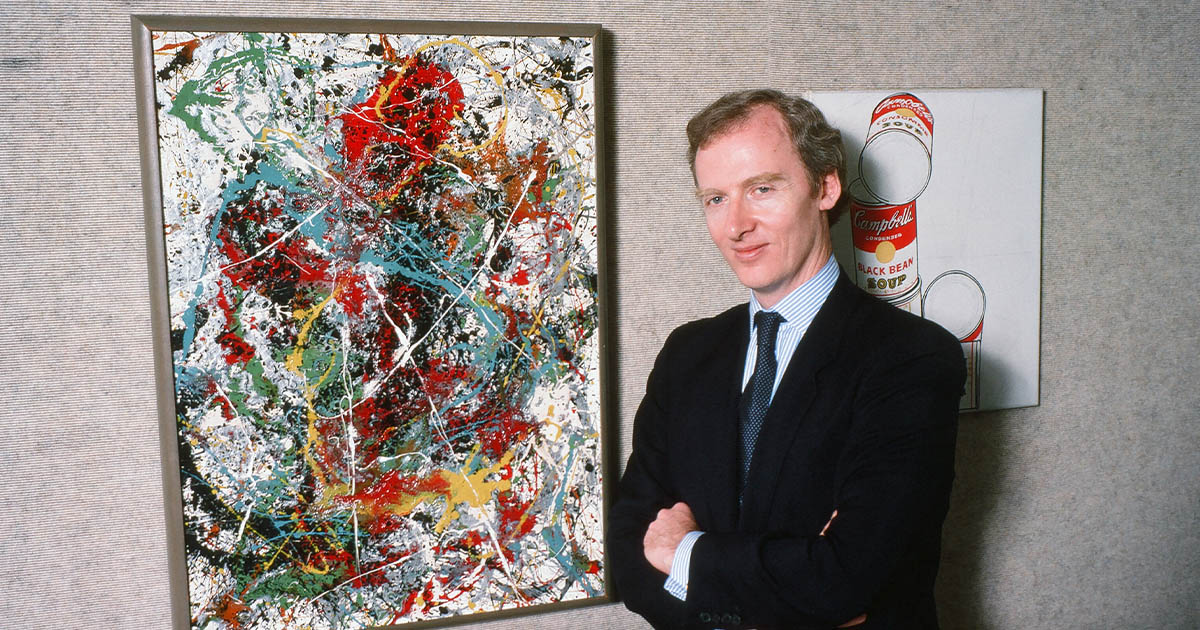

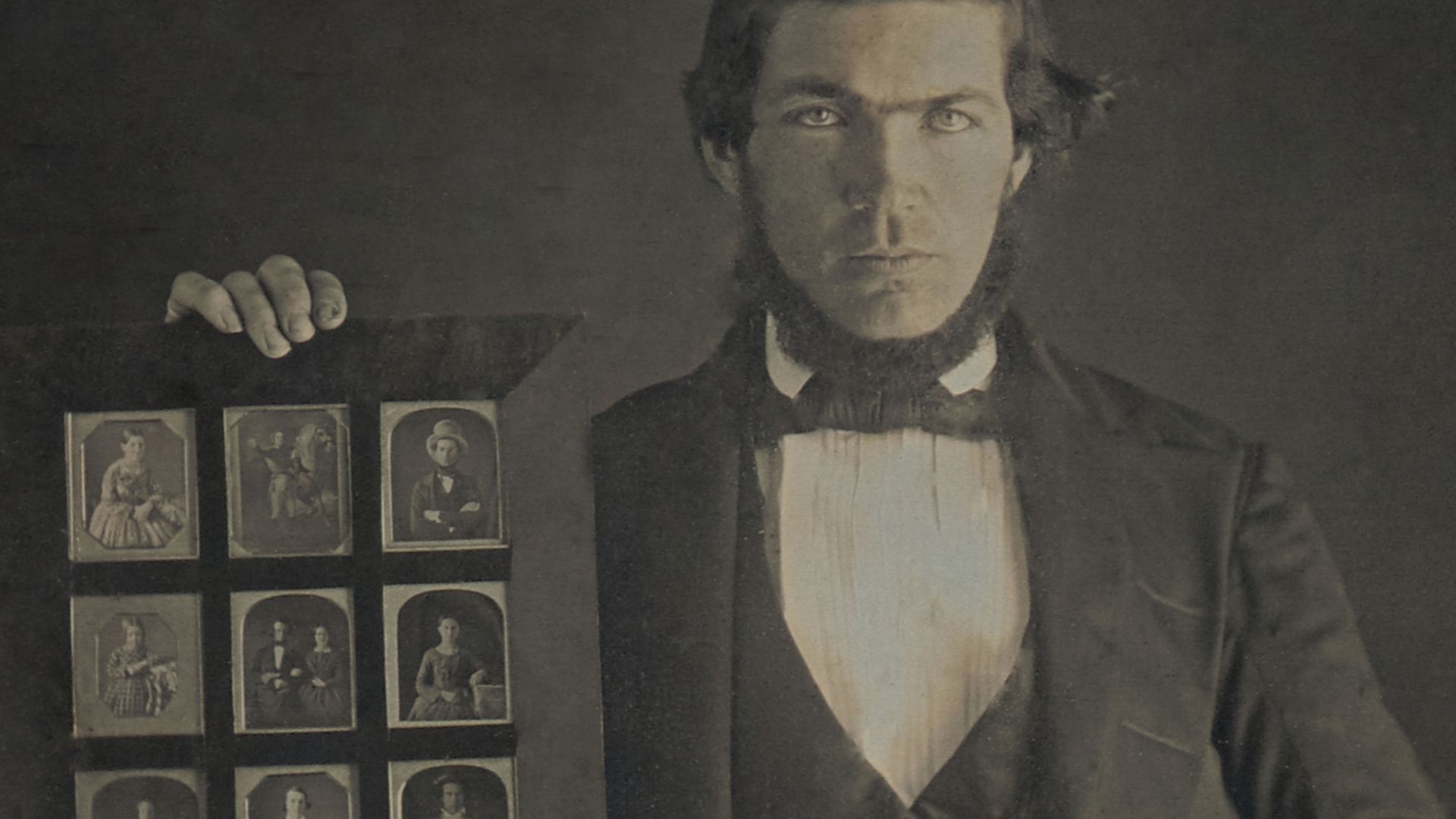

Daguerreotypist

Early photographers known as daguerreotypists practiced a demanding process introduced in 1839. Creating images required polishing silver plates and exposing them to iodine vapors before careful development. As cheaper and faster photographic methods appeared later in the 19th century, the profession faded.

UnknownUnknown Restored by Wcamp9, Wikimedia Commons

UnknownUnknown Restored by Wcamp9, Wikimedia Commons

Groom Porter

Within the English royal household, the Groom Porter oversaw gambling and lodging arrangements at court. Responsibilities included regulating card and dice games and supplying furniture for royal events.

Charlotta Ulrica Hilleström or Pehr Hilleström (d. 1816), Wikimedia Commons

Charlotta Ulrica Hilleström or Pehr Hilleström (d. 1816), Wikimedia Commons

Knitting Sheath Carver

Knitting sheath carvers produced wooden or bone tools that steadied needles during hand knitting. Common in rural Britain between the 17th and 19th centuries, these sheaths supported long hours of textile work. Many were intricately carved and exchanged as love tokens.

Peder Mørk Mønsted (1859-1941), Wikimedia Commons

Peder Mørk Mønsted (1859-1941), Wikimedia Commons

Rat Catcher

Modern pest control has now replaced their job, but used to be rat catchers hired to control infestations on farms and in towns. Their methods included dogs, traps, and poison. Some rat catchers publicly displayed their catches to prove effectiveness.

George Grantham Bain Collection, Wikimedia Commons

George Grantham Bain Collection, Wikimedia Commons

Alehouse Drawer

Alehouse drawers handled the daily task of drawing beer directly from wooden casks. The role sat at the heart of tavern life before modern bars existed. Drawers were sometimes accused of serving short measures.

Joseph Van Aken, Wikimedia Commons

Joseph Van Aken, Wikimedia Commons

Quill Cutter

Writing pens were shaped by quill cutters from feathers, and they did their job with careful precision. Their skill made literacy and recordkeeping possible across Europe. A single feather could yield multiple usable pens in practiced hands.

Paulus Lesire, Wikimedia Commons

Paulus Lesire, Wikimedia Commons

Cartwright

Building carts and wagons, cartwrights helped move goods, crops, and people in pre-industrial economies. Every design reflected local needs and terrain. Many craftsmen personalized their work with painted details or carvings.

Gaius Cornelius, Wikimedia Commons

Gaius Cornelius, Wikimedia Commons

Stagecoach Builder

Stagecoach builders combined woodworking, metalwork, and upholstery to create long-distance passenger and mail vehicles during the 18th and 19th centuries. Their workshops produced symbols of speed and progress, sometimes advertised as “flying machines”.

Tin Knocker

As skilled sheet-metal workers, tin knockers fabricated tinware, ducts, and roofing before factory production took over. Unlike roaming tinkers, they usually worked from shops or construction sites. The craft thrived during the 18th and 19th centuries, but mass production replaced it.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

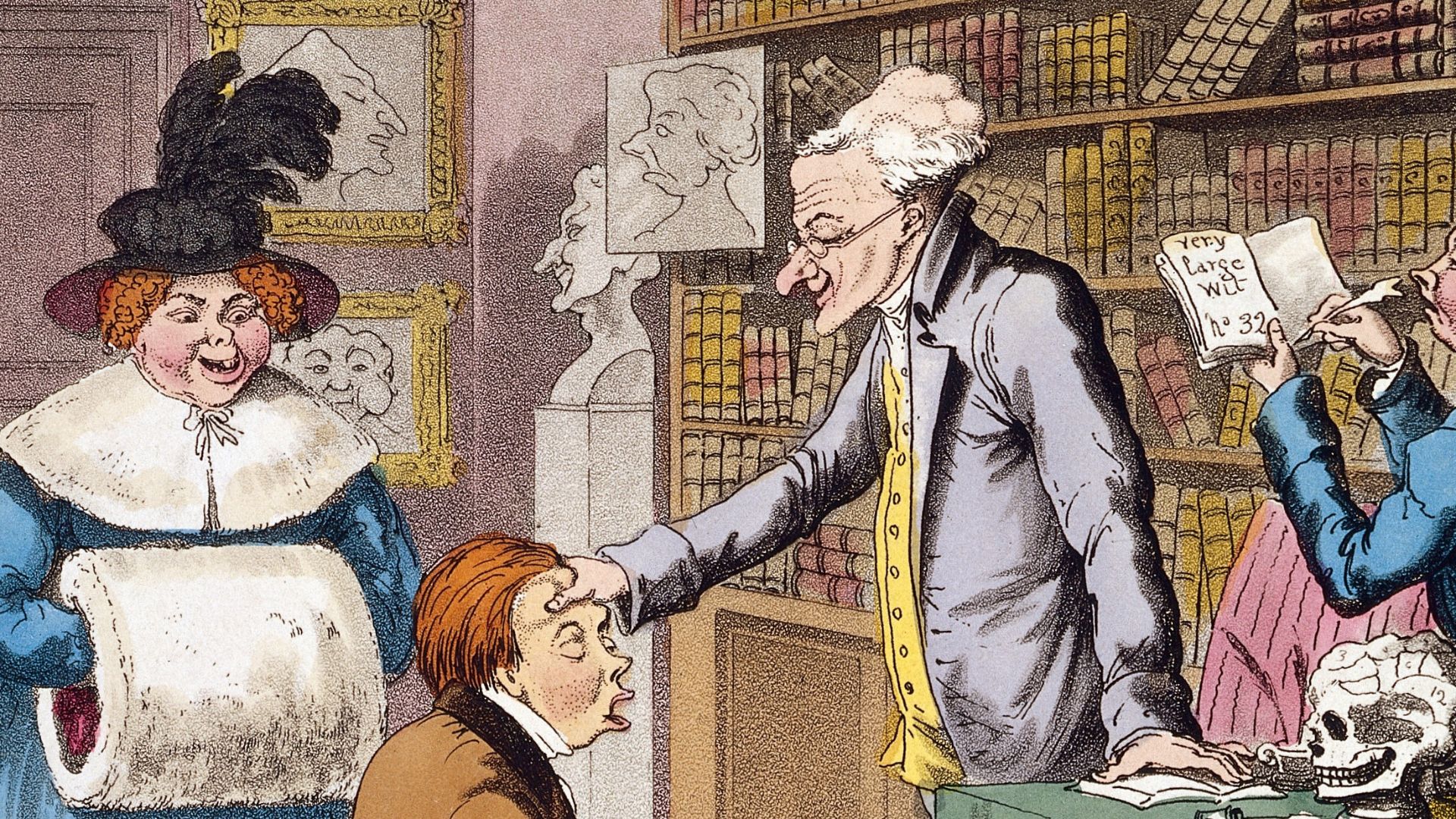

Phrenologist

Phrenologists claimed they could read personality and intelligence by examining skull shape. This practice became popular during the 19th century and influenced hiring decisions and criminology. Decorative phrenology heads appeared in parlors as conversation pieces.

George Cruikshank, Wikimedia Commons

George Cruikshank, Wikimedia Commons

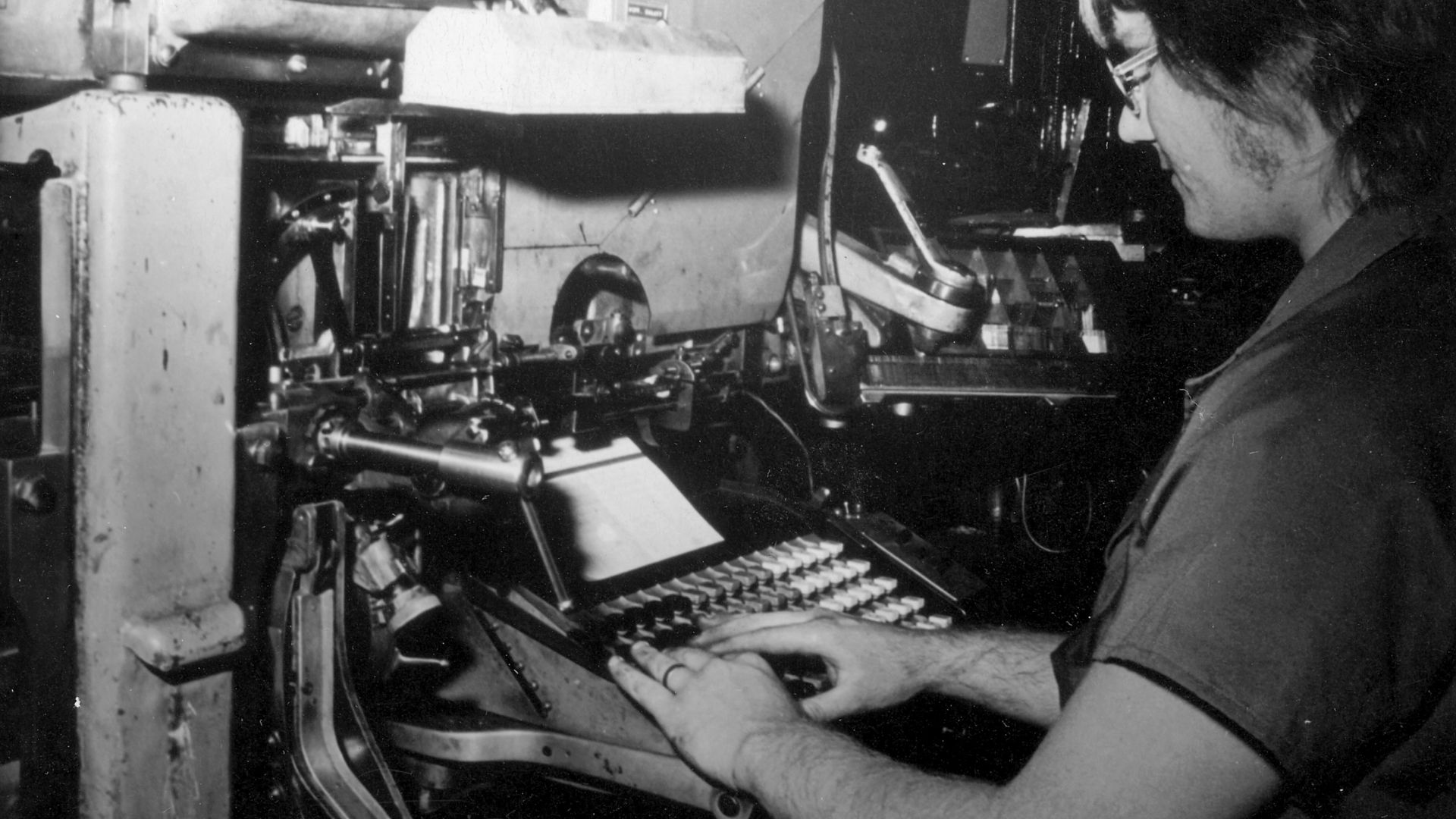

Linotype Operator

Prior to digital layouts, the Linotype machine reshaped printing by casting full lines of text in molten metal, a breakthrough introduced in 1884. Operators worked daily with hot lead, earning the nickname “hot-metal men”. Newspapers and books printed faster than ever until phototypesetting and digital publishing took over.

Queensland State Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Queensland State Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Alehouse Fiddler

Music once filled medieval and early modern taverns thanks to alehouse fiddlers who entertained drinkers with live tunes. Payment rarely came as wages and more often meant meals or ale. However, taverns became regulated businesses, and music shifted toward theaters and concert halls.

Coastal Elite from Halifax, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

Coastal Elite from Halifax, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

Lampblack Maker

Lampblack makers produced soot used in inks and cosmetics by capturing residue from burning oil or resin. The work was messy yet essential for centuries. With special formulations, lampblack was also used to create dark smoke effects.

Rag-And-Bone Man

Urban streets once echoed with shouted calls from rag-and-bone men collecting unwanted rags and household items for resale or reuse. Traveling by horse-drawn cart, they formed an informal recycling network in 19th and early 20th-century Britain.

Chris Denny, Wikimedia Commons

Chris Denny, Wikimedia Commons

Saltpetre Man

Gunpowder production depended on saltpetre men who gathered nitrates from decomposed organic matter between the Middle Ages and the 18th century. Harvesting sometimes involved scraping stable walls or cellar surfaces. The work was intrusive and labor-intensive.

Satirdan kahraman, Wikimedia Commons

Satirdan kahraman, Wikimedia Commons

Crossing Sweeper

Busy city crossings once relied on crossing sweepers to clear mud and horse manure for passing pedestrians. Working independently, they survived on small tips rather than wages. Many sweepers were children or among the poorest residents.

William Powell Frith, Wikimedia Commons

William Powell Frith, Wikimedia Commons

Dog Whipper

Maintaining order during church services once fell to dog whippers in medieval and early modern England. Armed with a whip or long stick, they chased stray animals from sanctuaries. Changes in animal control and church practices eliminated the position, though some churches later kept ceremonial dog whips as historical curiosities.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Link-Boy

After sunset in 17th and 18th-century cities, link-boys earned money by carrying flaming torches to guide pedestrians through unlit streets. Wealthy patrons relied on them for safer passage. With gas lamps and later electric lighting, the job disappeared.

Joshua Reynolds, Wikimedia Commons

Joshua Reynolds, Wikimedia Commons

Powder Horn Carver

Gunpowder once traveled in handcrafted containers made by powder horn carvers. Using a cow or ox horn, they shaped and decorated storage pieces with carvings or inscriptions. Many horns became personal keepsakes marked with battles or mottos. Cartridge ammunition in the 19th century rendered the craft obsolete.

Pierre André Leclercq, Wikimedia Commons

Pierre André Leclercq, Wikimedia Commons

Spinning Jenny Operator

Textile production changed dramatically after 1764, when the Spinning Jenny allowed operators to spin multiple threads at once. These workers became essential during the Industrial Revolution, especially in early mills. Fear ran high among traditional hand-spinners, and some attacked operators.

David Dixon , Wikimedia Commons

David Dixon , Wikimedia Commons

Elevator Operator

Inside early high-rise buildings, elevator operators managed manual lifts by controlling stops and opening doors. From the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, the job was common in hotels and offices. Operators were trained for polite conversation.

The Library of Virginia from USA, Wikimedia Commons

The Library of Virginia from USA, Wikimedia Commons

Milk Roundsman

Morning routines once included the milk roundsman delivering fresh bottles directly to homes by cart or van. The job remained common through much of the 19th and 20th centuries. Children often left notes in empty bottles requesting extra milk or cream.

Keystone View Co, Wikimedia Commons

Keystone View Co, Wikimedia Commons

Rushlight Maker

Before affordable candles reached most homes, rushlight makers supplied cheap household lighting across medieval Europe. The process involved dipping dried rushes into animal fat or grease. These lights burned unevenly and smoked heavily, earning the nickname “poor man’s candles”.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Gunflint Knapper

Sharp-edged flints used in muskets and pistols came from gunflint knappers who shaped stone through skilled knapping. From the 17th to the early 19th centuries, their work supported armies and everyday firearms. Experienced knappers could produce thousands weekly.

All rights reserved, Amy Downes, 2011-08-03 15:30:14, Wikimedia Commons

All rights reserved, Amy Downes, 2011-08-03 15:30:14, Wikimedia Commons

Town Crier

News once traveled by voice through town criers who publicly announced laws and proclamations in busy squares. The role thrived in medieval and early modern Europe before newspapers and widespread literacy. Each announcement traditionally ended with “Oyez, Oyez,” meaning “Hear ye”.

Jonathan Kington , Wikimedia Commons

Jonathan Kington , Wikimedia Commons