Cash Before Clock

Most luxury watch enthusiasts follow a practical guideline. Take any timepiece's price tag and multiply by ten—that's roughly what you should earn annually before buying it. Simple formula, eye-opening reality.

IWC Schaffhausen

An American engineer named Florentine Ariosto Jones founded IWC in 1868, bringing industrial efficiency to Swiss tradition, and that fusion still defines the company today. Their manufacturing approach blends Germanic precision with Swiss artistry, creating watches that feel different from typical Swiss luxury.

IWC Schaffhausen (Cont.)

The Portugieser collection features movements so large they barely fit in wristwatch cases. These watches have soft iron inner cases protecting against magnetic fields, seven-day power reserves, and perpetual calendars programmed until 2100. Priced $4,000–$15,000, they demand $150,000–$250,000 in earnings.

TAG Heuer

Steve McQueen strapped on a Monaco for Le Mans, instantly cementing TAG Heuer's cool factor, but the brand's motorsport DNA runs much deeper. It was the official timekeeper of Formula 1 from 1992 to 2005, developing chronographs that could measure lap times to 1/1000th of a second.

TAG Heuer (Cont.)

This precision comes from decades of racing partnerships where milliseconds determine million-dollar victories. Around $2,000–$6,000 gets you genuine racing heritage. TAG Heuer showed 13.29% growth in secondary market prices, proving that accessible luxury can still appreciate.

Juho Eskelä, Wikimedia Commons

Juho Eskelä, Wikimedia Commons

Breitling

Forget fashion—Breitling builds instruments that save lives. Their Emergency watch contains a genuine dual-frequency emergency locator beacon that has triggered real rescue operations for downed pilots and stranded adventurers. The brand has a strong partnership with SWISS International Air Lines. For $3,000–$8,000, you can buy into aviation's inner circle.

Breitling (Cont.)

The Navitimer's slide-rule bezel performs 40 different calculations essential for flight navigation, including fuel consumption and distance conversions. Besides, you will have to pay $30,000–$67,000+ for top-end models such as Premier B21 Chronograph Tourbillon, Navitimer, or diamond/gold editions.

Torsten Bolten, Wikimedia Commons

Torsten Bolten, Wikimedia Commons

Omega

Omega demonstrated 27.81% price increases in the pre-owned market over five years, making it one of the smartest entry points into luxury watchmaking. Its moon landing credentials aren't just marketing fluff. NASA put the Speedmaster through brutal tests, including extreme temperatures, vibrations, and pressure changes.

Torsten Bolten, Wikimedia Commons

Torsten Bolten, Wikimedia Commons

Omega (Cont.)

The financial reality? You're looking at $4,000–$8,000 for a quality Omega, which translates to needing roughly $75,000–$100,000 annually if you follow the conservative 5–10% rule. It is said that James Bond has been wearing Omega since 1995.

FrankWilliams at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

FrankWilliams at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

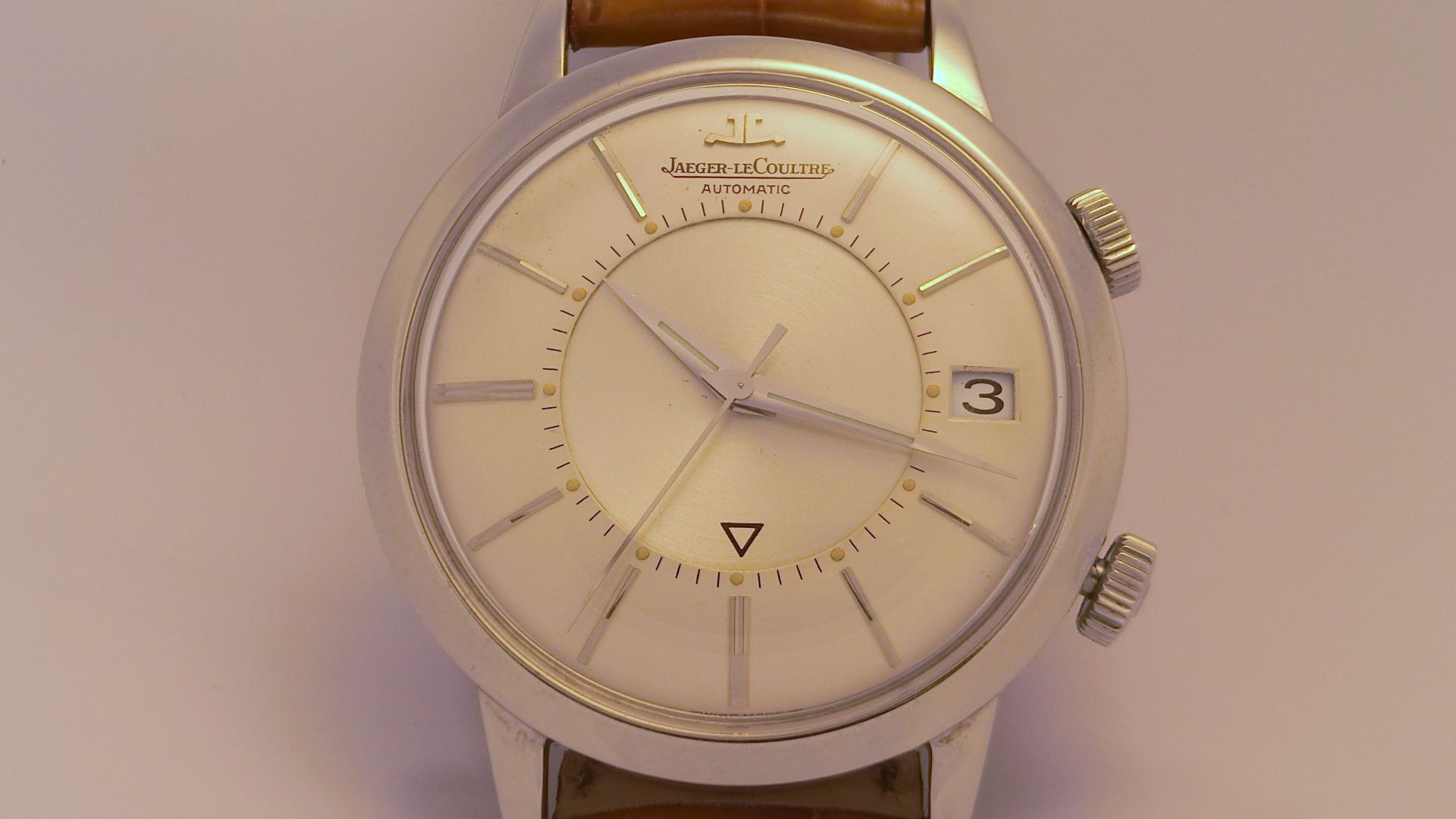

Jaeger-LeCoultre

JLC is often referred to as a "Watchmaker's Watchmaker" since they provide high-quality calibers to some of the most prestigious names in the business. This includes Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin. So, you're purchasing from the company that actually makes movements for brands charging twice as much.

Jaeger-LeCoultre (Cont.)

The Reverso originated from a 1931 challenge when British polo players needed protection for their watch faces. JLC's solution? A completely reversible case that became an Art Deco icon. It has developed over 1,242 in-house calibers. The price ranges from $8,000–$25,000.

Provo rossi, Wikimedia Commons

Provo rossi, Wikimedia Commons

Rolex

The secondary market tells Rolex's real story: specific models trade above retail price years after purchase, creating waiting lists that stretch for decades. At $8,000–$40,000 ($300,000—$500,000+ income), you can access manufacturing precision that treats luxury watches like mission-critical equipment.

Rolex (Cont.)

Rolex achieved 27.59% price increases in the pre-owned market over five years, but demand outstrips supply. This scarcity isn't artificial. The company produces roughly 1 million watches annually while maintaining standards that reject movements for microscopic imperfections invisible to human eyes.

Cartier

Louis Cartier revolutionized timekeeping in 1904 when his friend Alberto Santos-Dumont complained about fumbling with pocket watches while piloting early aircraft. The resulting Santos watch became the first men's wristwatch designed for practical use, turning timepieces from feminine jewelry into masculine tools.

Cartier (Cont.)

Cartier watches displayed 39.06% value gains in the pre-owned market over five years. The Tank's clean lines, the Ballon Bleu's floating crown, and the Panthere's predatory elegance represent pure design philosophy. Expect $5,000–$20,000 price tags requiring $200,000–$400,000 annual earnings.

Panerai

Mussolini's navy commandos wore Panerai watches during WWII underwater sabotage missions, strapping oversized timepieces outside their diving suits for legibility in murky Mediterranean waters. These were classified military equipment manufactured under Italian naval contracts with earlier Panerai models using luminous dials containing radioactive radium.

Panerai (Cont.)

Modern Panerai maintains that utilitarian DNA while commanding $4,000–$15,000 prices ($150,000–$300,000 per year). The signature 44-47mm cases still dwarf most wrists, but that oversizing serves functional purposes: maximum dial legibility and extended power reserves up to eight days.

Daniel Zimmermann from Bayern, Deutschland (Germany), Wikimedia Commons

Daniel Zimmermann from Bayern, Deutschland (Germany), Wikimedia Commons

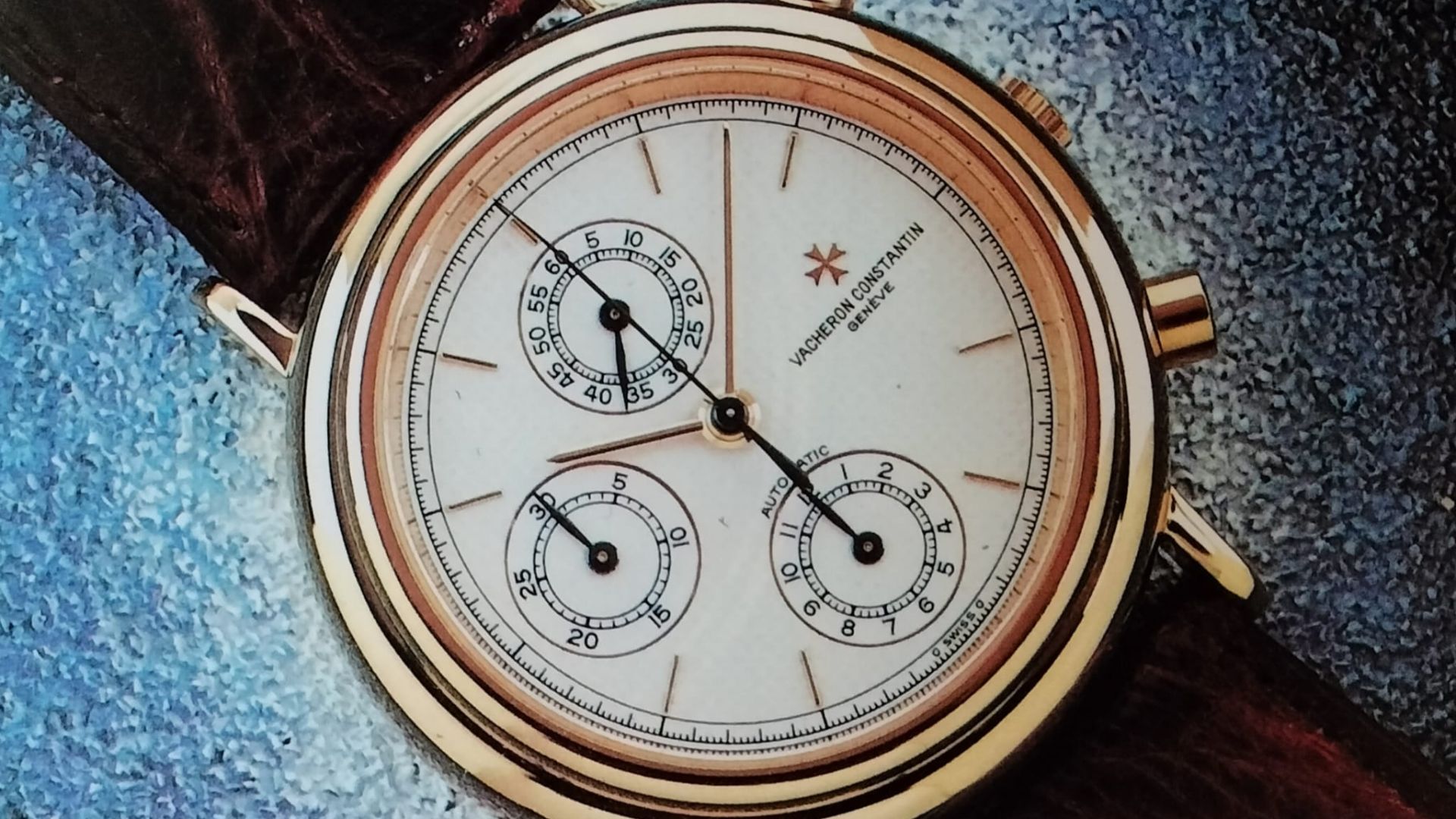

Vacheron Constantin

Vacheron Constantin has been in continuous operation since 1755, making it the oldest watch company in the world that has never ceased production. Their Geneva workshops preserve techniques dating back centuries. Here, entry-level pieces start around $12,300 for a Fiftysix.

Vacheron Constantin (Cont.)

Besides, most collections range $20,000–$100,000+. But you're not just buying a watch, you're acquiring membership in an exclusive club where Francois Constantin's motto, "Do better if possible, and that is always possible," drives perfectionist standards.

Patek Philippe

Geneva's most secretive manufacturer operates under a simple philosophy: they never sell watches to customers, only to future caretakers. The Patek Philippe Nautilus with Tiffany Blue dial became the most expensive wristwatch ever sold at auction, fetching $6.5 million at Phillips in 2021.

Patek Philippe (Cont.)

The financial commitment reflects this reality. Patek Philippe's average retail price was calculated at around $49,726 in 2024, with waiting lists extending decades for popular models. You'll need $800,000–$2,000,000+ annual income to justify $50,000–$500,000+ purchases.

Audemars Piguet

To afford an Audemars Piguet watch, another highly prestigious name in Swiss luxury horology, you should follow the industry guideline of spending no more than 10% of your annual pre-tax income on a single luxury watch. Audemars Piguet is a cornerstone of the “Holy Trinity” of watchmaking.

Audemars Piguet (Cont.)

It commands high entry prices, especially for its legendary Royal Oak series. The Royal Oak Quartz 33mm for women typically retails around $18,700, and market prices can reach above $19,000. Additionally, the mid-size Royal Oaks (automatic) range from $20,000–$35,000.

Richard Mille

Rafael Nadal wears his Richard Mille RM 027 during tennis matches. This $1,050,000 timepiece weighs less than a slice of bread yet survives violent racquet impacts that would shatter conventional luxury watches. The cheapest Richard Mille currently trades around $70,000 for the rectangular RM 016.

Richard Mille (Cont.)

Besides, the first "Richard Mille"-looking piece, the RM 005, costs $100,000. Most models range $200,000–$1,000,000+, demanding multi-million dollar annual incomes for responsible ownership ($1,000,000–$10,000,000). Richard Mille engineers wearable machines using Carbon TPT, titanium alloys, and sapphire crystal cases.