A tiny ownership detail has suddenly taken over the sale

This home sale was expected to be routine. Then a small detail surfaced during paperwork review: the homeowner is listed as a 1% owner on another property. That single line of text is now dominating conversations with lenders and tax professionals.

Why a 1% stake doesn’t feel harmless anymore

One percent sounds negligible, but real estate law doesn’t treat ownership symbolically. Deeds don’t grade on a curve. Any ownership interest, no matter how small, is still legally real—and it shows up clearly during a home sale.

Adrian S Pye , Wikimedia Commons

Adrian S Pye , Wikimedia Commons

How people usually end up with a 1% interest

Parents are often pulled into a child’s purchase to help it happen—sometimes through cash help, sometimes through paperwork. In the National Association of Realtors’ Profile of Home Buyers and Sellers, 25% of first-time buyers used a gift or loan from a relative or friend for their downpayment. That kind of family help is common, but it can come with strings later when lenders and tax rules look at what you technically own.

Why this only comes up when selling

Selling a home triggers deep review. Title companies, lenders, and tax advisors all examine ownership history at once. That’s usually when small, forgotten interests like a 1% stake resurface—and when panic sets in.

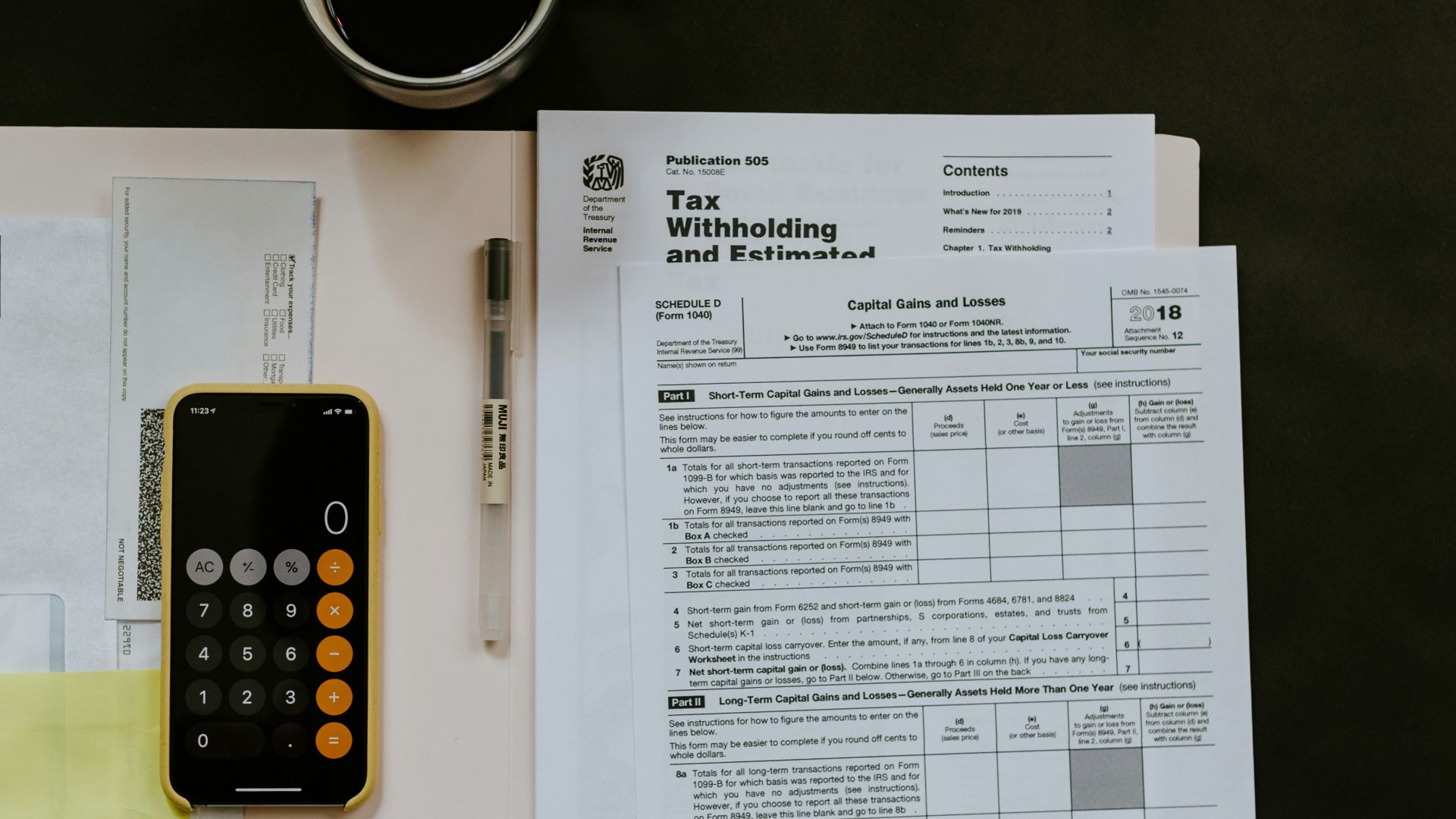

The tax break now under scrutiny

The concern centers on the home-sale capital gains exclusion, one of the most valuable tax benefits available to homeowners. Under IRS rules, up to $250,000 in profit can be excluded for single filers, and up to $500,000 for married couples filing jointly.

MBisanz talk, Wikimedia Commons

MBisanz talk, Wikimedia Commons

Why losing that exclusion is such a big deal

According to FHFA’s all-transactions House Price Index, U.S. home prices rose about 55% from late 2019 to late 2024, meaning today’s gains are often much larger than sellers expect. Losing the exclusion can mean federal capital gains taxes of 15% to 20%, plus possible state taxes.

Infrogmation of New Orleans, Wikimedia Commons

Infrogmation of New Orleans, Wikimedia Commons

The rule behind the exclusion

To qualify, the homeowner must have owned and lived in the property for at least two of the five years before the sale. The rule sounds simple, but real-life ownership situations often complicate how it’s applied.

Why another property interest raises flags

When someone owns more than one property—even just 1%—professionals need to confirm which home truly served as the primary residence. That review becomes stricter when large gains are involved.

The key clarification most people don’t hear right away

Owning 1% of another property does not automatically disqualify someone from the capital gains exclusion. The IRS focuses on use and occupancy, not the number of properties listed on a deed. Panic usually comes from assuming ownership alone already ruined the tax break.

Why the warning still isn’t meaningless

Although ownership alone doesn’t eliminate the exclusion, it narrows the margin for error. Certain actions, when combined with multiple properties, can create real and measurable tax consequences.

How that same 1% can matter during a mortgage renewal

Even if the parent is not selling, a mortgage renewal or refinance can trigger similar scrutiny. Under Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac underwriting guidelines, lenders may count the full monthly payment of a co-owned property toward a borrower’s debt.

When a child’s mortgage suddenly counts against the parent

During renewal, lenders may include some or all of the child’s mortgage when calculating debt-to-income ratios. Without proof the child alone has paid for at least twelve months, the parent’s borrowing profile can look weaker.

Timing is the biggest risk factor

Problems usually arise when the homeowner moves out long before selling, delays the sale, or changes how the property is used. These timing issues can weaken the claim that the home remained the primary residence.

Renting before selling can trigger taxes

If the home is rented after the owner moves out, depreciation becomes allowable. When the home is sold, the IRS can require depreciation recapture, often taxed up to 25 percent.

Why the 1% ownership makes this worse

Owning another property makes it harder to argue that the sold home was the only residence in use. It doesn’t create new tax rules, but it increases scrutiny when timelines become messy.

Clyde Charles Brown, Wikimedia Commons

Clyde Charles Brown, Wikimedia Commons

This can matter even without living elsewhere

The homeowner does not need to have lived in the other property for it to raise questions. Title records alone can prompt closer review, making documentation critical.

Delays can create indirect tax costs

When ownership questions slow a sale, closings can slip into a new tax year. That can increase taxable income or disrupt planned tax strategies.

What does not usually cause extra tax

Helping a child qualify for a mortgage is not a taxable event. Owning a small percentage alone does not trigger capital gains tax, and exclusions are not revoked casually.

Getting out of the 1% is harder than people expect

Removing a parent’s name usually requires the child to refinance the mortgage. Deed changes alone often do not remove lender exposure.

Why this situation feels so destabilizing

Most homeowners expect selling to be procedural. Discovering mid-sale that an old decision could affect taxes creates fear because the stakes are high.

BrendelSignature at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

BrendelSignature at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

How bad the worst case could be

If the exclusion were lost, gains could be taxed at federal capital gains rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%, plus possible state taxes and depreciation recapture.

The outcome for most sellers

In many cases, the exclusion still applies once facts are reviewed carefully. Preparation, timing, and professional guidance usually determine the outcome.

The real lesson

A 1% ownership stake doesn’t automatically cause a tax disaster—but it can turn small missteps into expensive ones. Tiny property interests deserve serious attention.

You Might Also Like:

The Retirement Mistake 85% of Gen X and Boomers Wish They Could Undo